La Noche Boca Arriba

By Julio Cortazar

Halfway down the long hotel passageway he thought it must already be late, so he hurried out to the street and pulled the motorcycle from the corner where the porter next door let him keep it.

At the jewelry shop on the corner he saw it was ten to nine; he would arrive with plenty of time wherever he was going. The sun seeped through the tall downtown buildings, and he—because for himself, for riding and thinking, he had no name—mounted the machine, savoring the ride. The motorcycle purred between his legs, and a fresh wind whipped his pants.

He passed by the ministries (the pink one, the white one) and the series of shops with brilliant windows along Central Avenue. Now he was entering the most enjoyable part of the ride, the true stroll: a long street lined with trees, little traffic, and spacious villas whose gardens spilled out to the sidewalks, barely separated by low hedges. Perhaps a little distracted, but keeping to the right as he should, he let himself be carried along by the smoothness, by the slight exhilaration of a day that had barely begun. Maybe that involuntary relaxation kept him from foreseeing the accident. When he saw the woman standing on the corner suddenly dart into the street despite the green lights, it was already too late for easy solutions. He braked hard with foot and hand, swerving left; he heard the woman’s scream, and with the impact lost sight of everything. It was like falling asleep all at once.

He jolted awake. Four or five young men were pulling him out from under the motorcycle. He tasted salt and blood, one knee hurt, and when they lifted him he screamed because he couldn’t bear the pressure on his right arm. Voices that didn’t seem to belong to the faces hanging over him encouraged him with jokes and assurances. His only relief was hearing confirmation that he had been in the right crossing the intersection. He asked about the woman, trying to control the nausea rising in his throat. While they carried him face-up to a nearby pharmacy, he learned that the one causing the accident had nothing worse than scratches on her legs. “You barely grazed her, but the impact threw the bike sideways…” Opinions, memories, slowly, carry him on his back, that’s it, and someone in a white coat giving him a swallow of something that eased him in the dimness of the little neighborhood pharmacy.

The police ambulance arrived in five minutes; they laid him on a soft stretcher where he could lie comfortably. Perfectly lucid, but knowing he was under the effects of a terrible shock, he gave his details to the officer accompanying him. His arm hardly hurt at all; blood dripped from a cut over his eyebrow and ran down his whole face. Once or twice he licked his lips to drink it. He felt fine, it was an accident, bad luck; a few weeks of rest and that would be it. The officer told him the motorcycle didn’t look too badly damaged. “Of course,” he said. “It landed right on top of me…” Both of them laughed, and at the hospital the officer shook his hand and wished him good luck. The nausea was returning little by little; as they wheeled him on a gurney down a corridor beneath trees full of birds, he closed his eyes and wished he were asleep or chloroformed. But they kept him a long time in a room that smelled of hospital, filling out forms, removing his clothes, dressing him in a coarse, grayish shirt. They moved his arm carefully; it didn’t hurt. The nurses joked the whole time, and if it hadn’t been for the contractions in his stomach he would have felt almost happy.

They took him to radiology; twenty minutes later, with the still-wet plate resting on his chest like a black tombstone, they wheeled him into the operating room. A tall, thin man in white came over and studied the radiograph. A woman’s hands adjusted his head; he felt himself passed from one stretcher to another. The man in white approached again, smiling, something shining in his right hand. He patted his cheek and motioned to someone standing behind.

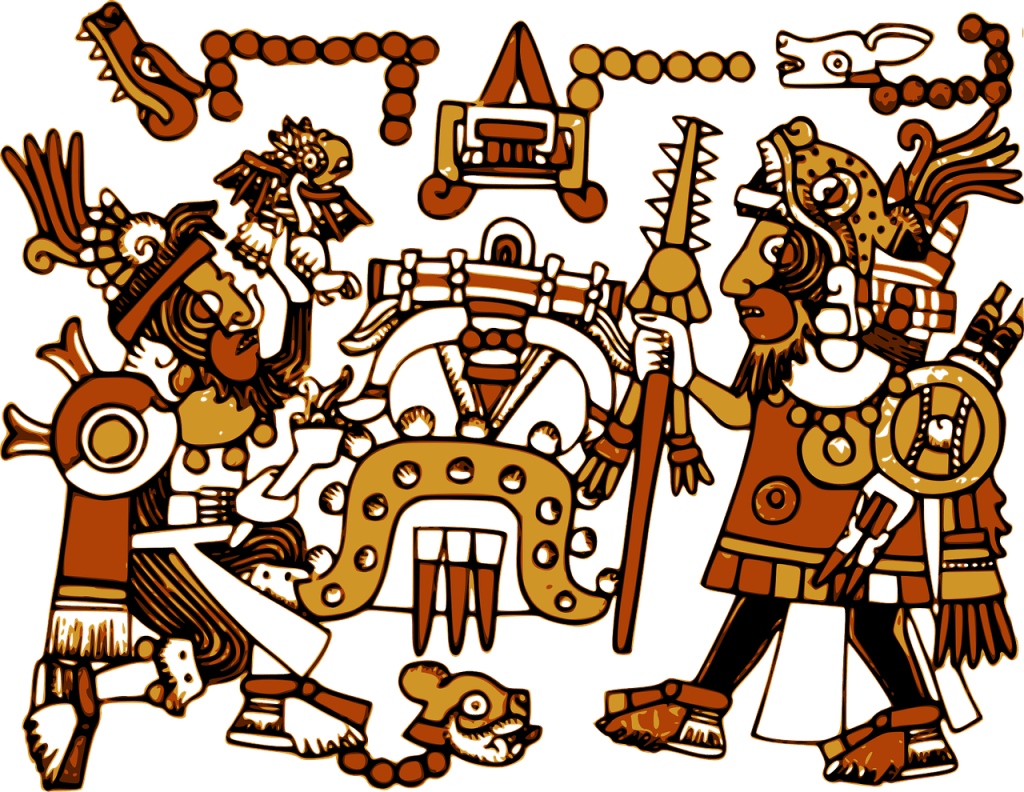

As a dream it was strange because it was full of smells, and he never dreamed smells. First a swamp smell, since to the left of the road the marshes began, the quagmires from which no one ever returned. But the smell ceased, and instead came a dense, dark fragrance like the night through which he moved, fleeing the Aztecs. And everything was so natural, he had to flee the Aztecs who were hunting men, and his only chance was to hide in the densest part of the jungle, taking care never to stray from the narrow path that only they, the Motecas, knew.

What tormented him most was the smell, as though, even in the absolute acceptance of the dream, something rebelled against what was not habitual, what until then had never taken part in the game. “It smells of war,” he thought, instinctively touching the stone blade threaded through his woven wool belt. An unexpected sound made him crouch and remain motionless, trembling. To be afraid was nothing strange; his dreams were full of fear. He waited, covered by the branches of a shrub and the starless night. Far away, probably on the other side of the great lake, campfires must be burning; a reddish glow colored that part of the sky. The sound was not repeated. It had been like a breaking branch. Perhaps an animal fleeing, like him, from the smell of war. He straightened slowly, sniffing. No sound could be heard, but the fear remained there like the smell, that sweetish incense of the Flower War. He had to go on, reach the heart of the jungle, avoiding the swamps. Groping, crouching every few moments to touch the harder ground of the path, he took a few steps. He would have liked to run, but the quagmires throbbed at his sides. On the dark trail he sought direction. Then he caught a gust of the scent he feared most and leapt forward in desperation.

“He’s going to fall out of bed,” said the patient in the next bed. “Don’t thrash around so much, friend.”

He opened his eyes and it was afternoon with the sun already low in the long hall’s windows. While trying to smile at his neighbor, he detached himself almost physically from the final vision of the nightmare. His arm, in plaster, hung from an apparatus of weights and pulleys. He felt thirsty, as if he had run for kilometers, but they would only let him wet his lips and take a sip. The fever was taking him gently, and he could have slept again, but he savored the pleasure of staying awake, eyes half-closed, listening to the other patients’ conversation, answering a question now and then. He saw a white cart stop beside his bed; a blonde nurse rubbed the front of his thigh with alcohol and gave him a thick injection connected to a tube that rose to a bottle of opalescent liquid. A young doctor came with a metal and leather apparatus that he fastened to his good arm to check something. Night was falling, and the fever was softly dragging him toward a state in which things had the shape as seen through theater binoculars, they were real and gentle and at the same time faintly repugnant; like watching a boring movie and thinking that, even so, it was worse outside; and staying.

A cup of marvelous golden broth arrived, smelling of leek, celery, parsley. A small piece of bread, more precious than a whole banquet, crumbled little by little. His arm didn’t hurt at all, and only on his eyebrow, where they had stitched him, did a quick, hot sting sometimes flash. When the windows opposite turned dark blue, he thought it would not be hard to sleep. A little uncomfortable on his back, but when he ran his tongue over his hot, dry lips he tasted the broth again and sighed with happiness, letting himself go.

At first there was confusion, a pulling toward himself of sensations dulled or mixed for an instant. He understood he was running in pitch darkness, though above him the sky crisscrossed with treetops less black than the rest. “The path,” he thought. “I’ve left the path.” His feet sank into a cushion of leaves and mud, and he could not take a step without the branches whipping his torso and legs. Gasping, knowing himself cornered despite the darkness and silence, he crouched to listen. Perhaps the path was close; at first daylight he would see it again. Nothing could help him find it now. The hand that unconsciously clutched the hilt of his dagger rose like a swamp scorpion to his neck, where his protective amulet hung. With scarcely a movement of his lips, he whispered the prayer of the corn that brings fortunate moons, and the supplication to the Very High One, the dispenser of Moteca blessings. But he felt at the same time his ankles sinking slowly into the mud, and waiting in the darkness of the unknown thicket became unbearable. The Flower War had begun with the moon and had already lasted three days and three nights. If he could take refuge deep in the jungle, abandoning the path beyond the swamp region, perhaps the warriors would not follow his trail. He thought of the many prisoners they must already have taken. But it was not the number that mattered, only the sacred time. The hunt would continue until the priests gave the signal to return. Everything had its number and its end; he was within the sacred time, on the other side of the hunters.

He heard the cries and leapt upright, dagger in hand. As if the sky were aflame on the horizon, he saw torches moving among the branches, very close. The smell of war was unbearable, and when the first enemy leapt at his throat he almost took pleasure in sinking the stone blade into his chest. Lights and joyous cries already surrounded him. He managed to slash the air once or twice more; then a rope caught him from behind.

“It’s the fever,” said the man in the next bed. “The same thing happened to me when they operated on my duodenum. Drink some water and you’ll sleep fine.”

Compared with the night from which he was returning, the warm half-light of the ward seemed delicious. A violet lamp watched high on the back wall like a guardian eye. He heard coughing, heavy breathing, sometimes a low-voiced conversation. Everything was pleasant and safe, without pursuit, without… But he didn’t want to go on thinking about the nightmare. There were so many things to amuse himself with. He began to look at the plaster on his arm, the pulleys that held it so comfortably in the air. They had left a bottle of mineral water on the night table; he drank from the neck, greedily. He could now make out the shapes of the ward, the thirty beds, the cupboards with glass doors. He probably didn’t have much fever left; his face felt cool. The eyebrow barely hurt, like a memory. He saw himself again leaving the hotel, taking out the motorcycle. Who would have thought it would end like this? He tried to fix the moment of the accident and it annoyed him to find a void there, a blank he could not fill. Between the crash and the moment they lifted him off the ground, a faint or whatever it was left him seeing nothing. And yet he had the feeling that void, that nothingness, had lasted an eternity. No, not even time, more as if in that void he had passed through something or traveled enormous distances. The crash, the brutal thrust against the pavement. Anyway, coming out of the black pit he had felt almost relief as the men raised him. With the broken arm, the blood from the split eyebrow, the bruised knee; with all that, relief at returning to daylight and feeling himself held and helped. And it was strange. Someday he would ask the doctor at the office. Now sleep was pulling him down again, pulling him gently downward. The pillow was so soft, and in his fevered throat the coolness of the mineral water. Perhaps he could really rest, without the damned nightmares. The violet light of the lamp up high was fading little by little.

Since he was sleeping on his back, the position in which he found himself again did not surprise him, but in contrast the damp smell, the oozing stone, closed his throat and forced him to understand. Useless to open his eyes and look in every direction; absolute darkness surrounded him. He tried to sit up and felt ropes on his wrists and ankles. He was staked to the floor on a surface of cold, damp stone slabs. The cold reached his naked back, his legs. Clumsily he sought contact with his amulet using his chin, and knew they had taken it from him. Now he was lost; no prayer could save him from the end. Far away, as though filtering through the dungeon stones, he heard the festival drums. They had brought him to the teocalli; he was in the prison cells of the temple awaiting his turn.

He heard a hoarse cry rebound off the walls. Another cry ending in a moan. It was he who was crying in the darkness, crying because he was alive, his whole body defending itself with cries against what was coming, the inevitable end. He thought of the companions who would fill other cells, and of those already climbing the steps of the sacrifice. He cried again, stiflingly; he could hardly open his mouth, his jaws were clamped as if made of rubber and opened slowly, with endless effort. The screech of bolts shook him like a whip. Convulsed, writhing, he fought to free himself from the ropes biting into his flesh. His right arm, the strongest, pulled until the pain became intolerable and he had to give up. He saw the double door open, and the smell of torches reached him before the light. Barely covered by the ceremonial loincloths, the priests’ acolytes approached, looking at him with contempt. The torchlight glinted on sweaty chests, on black hair full of feathers. The ropes gave way, and in their place hot hands, hard as bronze, seized him; he felt himself lifted, still face up, dragged by the four acolytes who carried him along the passage. The torchbearers went ahead, dimly lighting the corridor with wet walls and such a low ceiling that the acolytes had to stoop. They were carrying him, carrying him; it was the end. Face up, a meter beneath the living rock ceiling that at times flared with the reflection of a torch. When stars appeared instead of the ceiling and the stairway blazing with cries and dances rose before him, it would be the end. The passage never ended, but it would end soon; suddenly he would smell open air full of stars, but not yet, they carried him endlessly in the red darkness, brutally dragging him, and he did not want it, but how to stop it if they had torn away his amulet, his true heart, the center of life.

He burst out of the hospital night into the high, gentle ceiling, into the soft shadow surrounding him. He must have cried out, but his neighbors slept quietly. On the night table the water bottle shimmered like a bubble, a translucent image against the bluish shadow of the windows. He gasped, seeking relief for his lungs, the oblivion of those images still clung to his eyelids. Each time he closed his eyes he saw them form instantly, and he sat up terrified yet at the same time rejoicing in knowing he was awake, that wakefulness protected him, that soon dawn would come, followed by good, deep sleep without images, without anything… It was hard to keep his eyes open; drowsiness was stronger than he. He made one last effort, reached with his good hand toward the water bottle; he did not reach it, his fingers closed on a void once more black, and the passage went on forever, rock after rock with sudden red flashes, and face up he whimpered faintly because the ceiling was about to end, it rose, opening like a mouth of shadow, and the acolytes straightened and from that height a waning moon fell upon his face where his eyes refused to see it, desperately closed and opened seeking to pass to the other side, to find again the protective ceiling of the ward. And each time they opened it was night and the moon, while they carried him up the stairway, now with his head hanging downward, and up above were the bonfires, the red columns of perfumed smoke, and suddenly he saw the red stone, shining with dripping blood, and the swinging feet of the victim they were dragging away to throw down the north staircase. With a last hope he clenched his eyelids tightly, moaning to wake up. For a second he thought he had done it, because once more he was motionless in bed, safe from the head-down swaying. But he smelled death, and when he opened his eyes he saw the blood-smeared figure of the sacrificer coming toward him with the stone knife in his hand. He managed to close his eyelids again, although he now knew he would not wake up, that he was awake, that the marvelous dream had been the other one, absurd, like all dreams, a dream in which he had walked along strange avenues of an astonishing city, with green and red lights burning without flame or smoke, with an enormous metal insect humming beneath his legs. In the endless falsehood of that dream they had also lifted him from the ground, someone had also approached him with a knife in hand, approaching him face up, face up with his eyes closed among the bonfires.

For the current translation, two AI models have been used: Chat GPT and Grok.

Leave a comment