La Biblioteca de Babel by Jorge Luis Borges

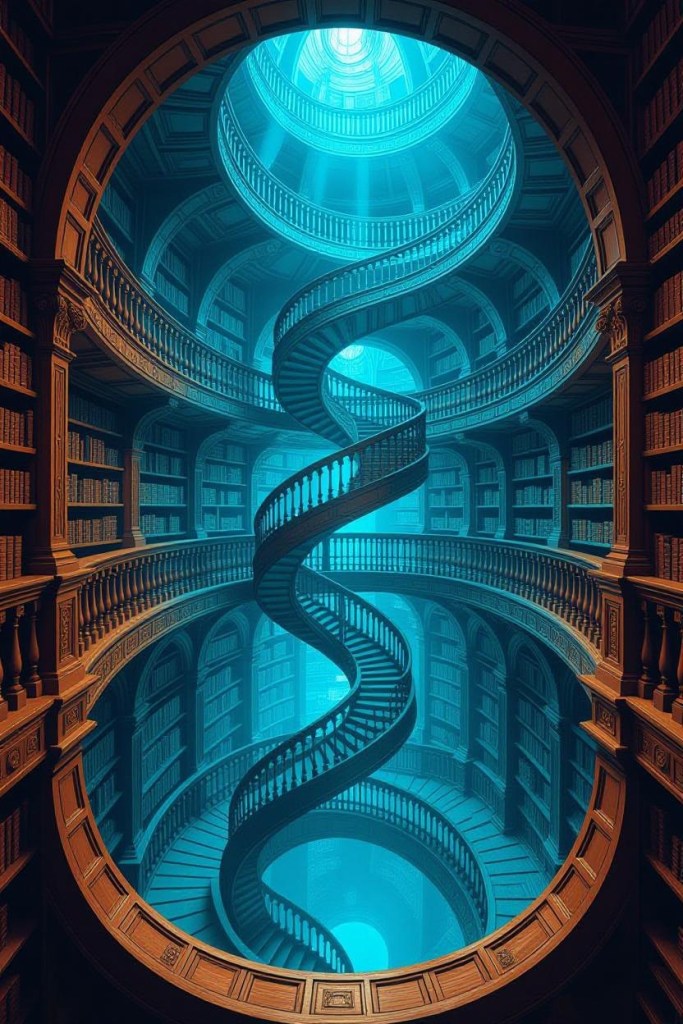

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite, number of hexagonal chambers, with vast ventilation shafts in their centres, encircled by low railings. From any hexagon, one can see the floors above and below: endlessly. The arrangement of the chambers is invariable. Twenty shelves, five long shelves per side, cover all but two of the walls; their height, which matches that of the floors, scarcely exceeds that of an ordinary librarian. One of the free walls opens onto a narrow hallway, which leads to another gallery, identical to the first and to all the rest. To the left and right of the hallway are two tiny chambers. One allows for sleeping upright; the other, for attending to final necessities. Through there twists the spiral staircase, plunging into the depths and rising toward the unknown. In the hallway, a mirror faithfully reflects appearances. Men often infer from this mirror that the Library is not infinite (if it were, why this illusory duplication?); I prefer to dream that its polished surfaces suggest and promise the infinite… Light comes from spherical balls called lamps. There are two in each hexagon, set crosswise. Their light is insufficient, unceasing.

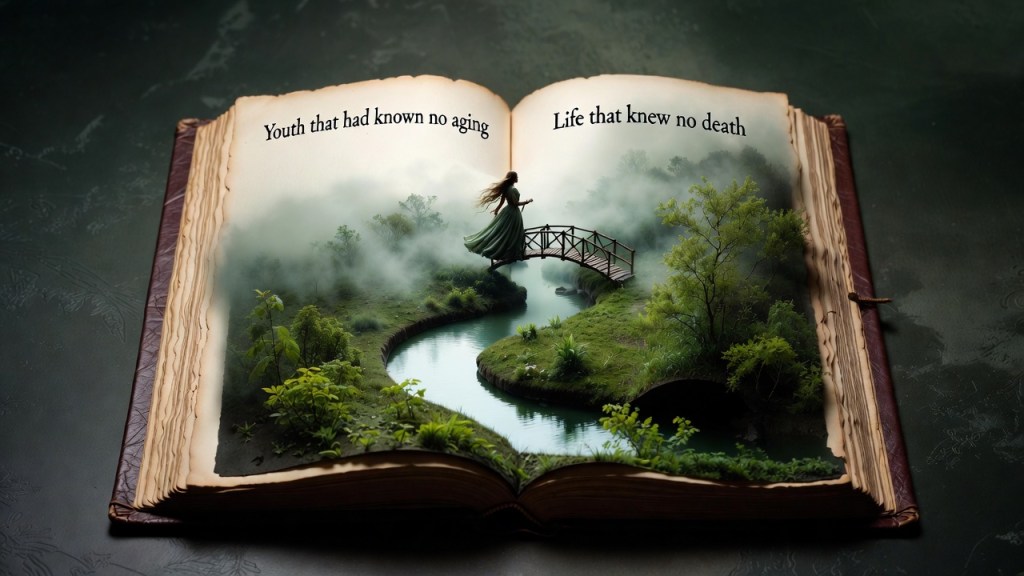

In my youth, like all men of the Library, I roamed its endless corridors, a pilgrim chasing a fabled book, the catalog of catalogs. Now that my eyes can barely decipher what I write, I prepare to die just a few chambers away from the hexagon where I was born. Once dead, pious hands will not fail to hurl me over the railing; my tomb will be the fathomless air; my grave will be the unfathomable air, my body tumbling through an endless wind, decaying, dissolving in the infinite fall. I proclaim the Library is endless. Idealists insist its hexagonal chambers are the necessary form of absolute space, or at least our soul’s perception of it, deeming triangular or pentagonal rooms unthinkable. Mystics, in their fevered visions, speak of a circular chamber, its walls lined with a single, seamless book, its spine unbroken, encircling eternity, a book they call God; their account is suspicious; their words obscure. For now, let me simply repeat the classic dictum: The Library is a sphere, its true centre any hexagon, its circumference forever out of reach.

Each hexagon wall holds five shelves; each shelf contains thirty-two uniform books; each book has four hundred and ten pages; each page, forty lines; each line, eighty black letters. There are also letters on the spine of each book; these letters neither hint nor herald what the pages’ content. I know that this disconnection once seemed mysterious. Before revealing the key (whose discovery, despite its tragic implications, is perhaps the central event of history), I wish to recall a few axioms.

First: The Library exists *ab aeterno*. No reasonable mind can question this truth, nor its corollary: the world’s eternal future. Man, the imperfect librarian, may be the work of chance or malevolent demiurges; the universe, with its elegant array of shelves, its enigmatic volumes, its endless staircases for the traveler, and latrines for the seated librarian, can only be the work of a god. To grasp the distance between the divine and the human, one need only compare these crude, trembling symbols that my fallible hand scratches upon the cover of a book with the letters within: punctual, delicate, jet-black, and inimitably symmetrical.

The second: the number of orthographic symbols is twenty-five. Three hundred years ago, this observation made it possible to formulate a general theory of the Library and to satisfactorily resolve the problem that no conjecture had ever deciphered: the formless and chaotic nature of nearly all books. One, which my father saw in a hexagon of circuit fifteen ninety-four, consisted of the letters MCV perversely repeated from the first line to the last. Another (much consulted in this region) is a mere labyrinth of letters, yet the penultimate page reads: “O Time, your pyramids.”

As is well known, a reasonable line or a single coherent statement may be surrounded by heaps of senseless cacophony, verbal thickets, and incoherence. (I know of a backwater region whose librarians repudiate the superstitious and vain habit of seeking meaning in books, equating it to the folly of searching for it in dreams or in the chaotic lines of the hand… They admit that the inventors of writing imitated the twenty-five natural symbols, but insist that their application is accidental, and that the books mean nothing in themselves. This judgment, as we shall see, is not entirely false.

For a long time, it was believed these impenetrable books corresponded to ancient or remote languages. It is true that the earliest men, the first librarians, spoke a language quite different from the one we use now; it is true that a few miles to the right the tongue is dialectical, and ninety floors above, incomprehensible. All this, I repeat, is true, but four hundred ten pages of unvarying MCV cannot correspond to any language, however dialectical or rudimentary. Some suggested that each letter could influence the next, and that the value of MCV on the third line of page seventy-one was not the same as that of MCV in another position on another page, but this dubious thesis did not prevail. Others thought of cryptographies; that hypothesis has been universally accepted, though not in the sense its inventors intended.

Five hundred years ago, the head of an upper hexagon came upon a book as confusing as the others, but containing almost two pages of homogeneous lines. He showed his discovery to a wandering translator, who declared that it was written in Portuguese; others said it was Yiddish. Before a century had passed, the language was established: a Samoyed-Lithuanian dialect of Guaraní, with inflections of Classical Arabic. The content was also deciphered: notions of combinatorial analysis, illustrated by examples of variations with unlimited repetition. These examples allowed a librarian of genius to discover the fundamental law of the Library. This thinker observed that all books, however varied, consist of the same elements: the space, the period, the comma, the twenty-two letters of the alphabet. He also noted a fact confirmed by all travelers: there are no two identical books in the vast Library. From these incontrovertible premises, he deduced that the Library is total, and its shelves contain all possible combinations of the twenty-odd orthographic symbols (a number, though vast, not infinite), in other words, everything that can be expressed, in all languages. Everything: the detailed history of the future, the autobiographies of archangels, the faithful catalog of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogs, the proof of the falsity of those catalogs, the proof of the falsity of the true catalog, the Gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary on that gospel, the commentary on the commentary of that gospel, the true account of your death, the translation of every book into every language, the interpolations of every book into all books, the treatise Bede might have written (but did not) on the mythology of the Saxons, the lost books of Tacitus.

When it was proclaimed that the Library encompassed all books, the first impression was one of extravagant joy. All men felt themselves masters of an intact and secret treasure. There was no personal or universal problem whose eloquent solution did not exist, somewhere in some hexagon. The universe was justified; the universe abruptly assumed the limitless dimensions of hope. At that time much was spoken of the Vindicaciones: books of apology and prophecy, which for all time vindicated the acts of every man in the universe and safeguarded prodigious secrets for his future. Thousands of the greedy abandoned their sweet natal hexagon and ascended the stairways, driven by the vain purpose of finding their Vindicacion. These pilgrims quarrelled in the narrow corridors, uttered obscure curses, strangled one another on the divine stairways, hurled misleading books to the depths of the tunnels, and fell to their deaths at the hands of men from distant regions. Others went mad… The Vindicaciones do exist (I have seen two that concern people of the future, perhaps not even imaginary), but the seekers did not remember that the possibility of a man finding his own, or some perfidious variation of it, is practically zero.

At that time, too, there was hope for the elucidation of the fundamental mysteries of humanity: the origin of the Library and of time. It is plausible that these grave mysteries can be explained in words; if the language of philosophers is insufficient, the multiform Library will have produced the unheard-of tongue required, with its vocabularies and grammars. For four centuries men have toiled among the hexagons… There are official seekers, inquisitors. I have seen them at work: they always arrive exhausted; they speak of a stairway without steps that nearly killed them; they speak of galleries and stairways with the librarian; occasionally they take the nearest book and leaf through it, searching for infamous words. Visibly, no one expects to discover anything.

Excessive hope was, as is natural, succeeded by an equally excessive depression. The certainty that some shelf in some hexagon contained precious books—and that these precious books were inaccessible—seemed almost intolerable. A blasphemous sect suggested that the searches cease and that all men shuffle letters and symbols until, by some improbable gift of chance, those canonical books might be constructed. The authorities were compelled to issue severe decrees. The sect vanished, yet in my childhood I saw old men who long hid in the latrines, with metal disks in a forbidden cup, faintly imitating the divine disorder.

Others, conversely, believed that the first imperative was to eliminate useless works. They invaded the hexagons, displayed credentials not always false, leafed through volumes with disdain, and condemned entire shelves. To their hygienic, ascetic fury is owed the senseless destruction of millions of books. Their name is execrated, yet those who lament the “treasures” their frenzy destroyed neglect two notorious facts. First: the Library is so enormous that any reduction of human origin is infinitesimal. Second: each copy is unique, irreplacable, but—as the Library is total—there are always several hundreds of thousands of imperfect facsimiles: works differing only by a single letter or a comma.

Contrary to popular opinion, I venture to suppose that the consequences of the depredations committed by the Purifiers have been exaggerated by the horror those fanatics inspired. They were driven by the delirium of conquering the books of the Crimson Hexagon: books of smaller format than the natural, omnipotent, illuminated, and magical.

We also know of another superstition from that time: that of the Man of the Book.

Somewhere, on some shelf in some hexagon (so men reasoned), there must exist a book that is the cipher and perfect compendium of all the others. Some librarian has read it and is therefore analogous to a god. In the language of this region, vestiges of that distant cult still persist. Many set out in pilgrimage to seek Him. For a century they exhausted in vain the most diverse directions. How could one locate the hallowed, secret hexagon that housed Him? Someone proposed a regressive method: to find Book A, first consult a Book B that indicates the place of A; to find B, first consult a Book C; and so on, to infinity… In such adventures I have squandered and consumed my years. It does not seem impossible to me that in some shelf of the universe there lies a total book. I pray to the unknown gods that a man—one man, even if it be thousands of years ago—may have examined and read it. If honor and wisdom and happiness are not for me, let them be for others. Let heaven exist, though my place be in hell. Let me be outraged and annihilated, but let there be, in one instant, in one being, justification for Your vast Library.

The impious affirm that nonsense is the natural state of the Library, and that reason — even the humble, pure coherence of a single line — is a nearly miraculous exception. They speak (I know well) of “the feverish Library, whose random volumes forever risk transforming into others, affirming all things, denying all things, and confusing all things, like a delirious divinity.”

These words, which not only denounce disorder but also exemplify it, prove their wretched taste and their desperate ignorance.

In truth, the Library contains every verbal structure, every variation permitted by the twenty-five orthographic symbols — but not one absolute piece of nonsense. It is useless to point out that the finest volume in the many hexagons I administer is titled Combed Thunder, and another The Plaster Cramp, and another Axaxaxas mlo.

These propositions, incoherent at first sight, are doubtless capable of some cryptographic or allegorical justification; that justification, being verbal, by definition already exists somewhere within the Library.

I cannot combine even a few characters — dhcmrlchtdj — that the divine Library has not already foreseen, and that, in some of its secret tongues, do not contain a terrible meaning.

No one can utter a single syllable that is not filled with tenderness and fear, that is not, in one of those languages, the powerful name of a god. To speak is to fall into tautology.

This useless, wordy epistle already exists — in one of the thirty volumes on one of the five shelves of one of the countless hexagons — and so does its refutation. (A number n of possible languages use the same vocabulary; in some of them, the symbol library allows the correct definition “ubiquitous and enduring system of hexagonal galleries,” but library also means bread or pyramid or any other thing, and the seven words that define it bear another meaning altogether.

You, who read me — are you sure you understand my language?)

Methodical writing distracts me from the present condition of men. The certainty that everything has already been written nullifies us, or turns us into phantoms.

I know of districts where young men prostrate themselves before the books and barbarously kiss their pages, though they cannot decipher a single letter.

Epidemics, heretical strife, and pilgrimages that inevitably degenerate into banditry have decimated the population. I believe I have mentioned the suicides, more frequent every year.

Perhaps age and fear deceive me, but I suspect that the human species — the only one — is on the verge of extinction, and that the Library will endure: illuminated, solitary, infinite, perfectly motionless, armed with precious volumes — useless, incorruptible, secret.

I have just written infinite. I have not inserted this adjective out of rhetorical habit; I mean that it is not illogical to think that the world is infinite. Those who judge it finite postulate that, in remote places, the corridors, stairways, and hexagons might inconceivably cease, which is absurd. Those who imagine it without limits forget that the possible number of books is itself finite.

I venture to suggest this solution to the ancient problem: the Library is unlimited and periodic. If an eternal traveler were to traverse it in any direction, he would discover, after centuries, that the same volumes repeat in the same disorder — which, if repeated, would be an order: the Order. My solitude rejoices in that elegant hope.

THE END

Leave a comment